By Cannibalizing Nearby Stromal Stem Cells, Some Breast Cancer Cells Gain Invasion Advantage

Cancer biologists and engineers collaborated on a device that could help predict the likelihood of breast cancer metastasis.

Enlarge

Enlarge

It’s a you-are-what-you-eat story starring breast cancer cells.

Researchers at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center and U-M College of Engineering have found that breast cancer cells that swallow up nearby stem cells take on some of their properties, enhancing their ability to invade other tissues throughout the body and seed secondary tumors, a process known as metastasis.

It started with an unexpected observation in the lab, and led to the development of a microfluidic device that researchers hope might help predict the likelihood that a breast cancer patient’s disease will spread.

The team’s findings appear in the journal Cell Reports.

“There’s a clinical need to better understand the metastatic process and how metastasis is influenced by the microenvironment of cells around a tumor. There is very little known on these kinds of interactions between cells,” says study senior author Celina Kleer, M.D., professor of pathology at Michigan Medicine and director of U-M’s breast pathology program. “About 20% of breast cancer patients develop distant metastases, for which there is no cure.”

There’s a clinical need to better understand the metastatic process and how metastasis is influenced by the environment of cells around a tumor.

Celina Kleer, M.D.

An intriguing observation

A few years ago, during an analysis of cells from breast cancer patients whose cancer had metastasized, Maria Gonzalez, M.S., a senior researcher in the Kleer lab and one of the study’s lead authors, discovered a population of cancer cells that had evidence of other cells inside them.

“The way it started was really interesting,” Kleer says. “We isolated mesenchymal stem cells and cultured them together with breast cancer cells to see what properties were induced or inhibited.

“And when we did flow cytometry, we consistently found that there was this small population of cells that had features of both types of cells,” she says.

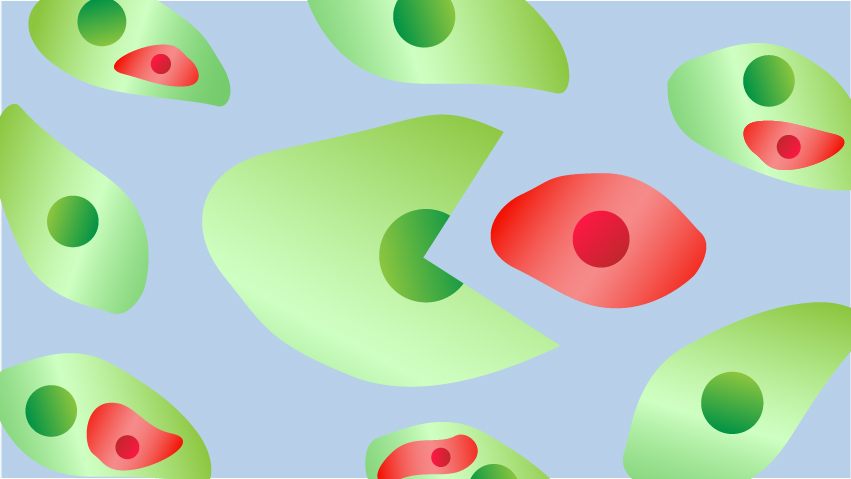

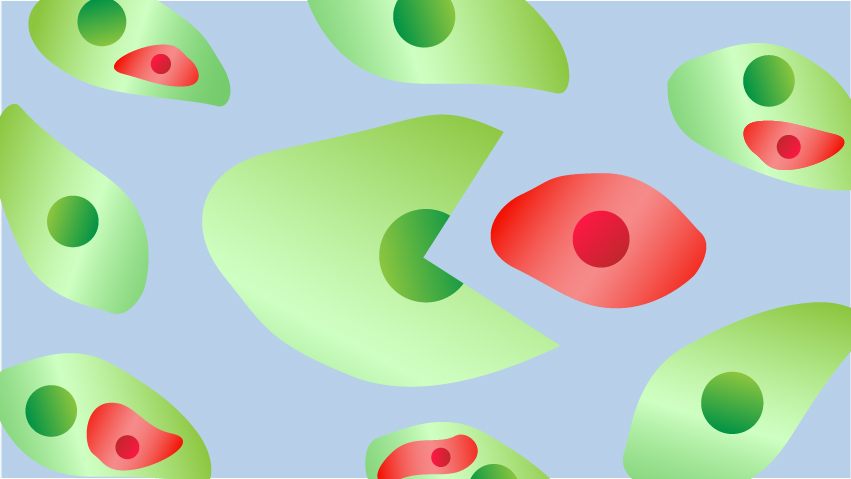

The mesenchymal stem cells had been labeled to glow red and the breast cancer cells made to fluoresce green.

“We were surprised to see a hybrid cell population that turned yellow and decided to investigate the biology behind this experimental observation,” she says.

Biologists and engineers team up

This led to further experiments to study what was happening in detail and how it affected the cancer cells’ aggressiveness.

The cancer researchers teamed up with scientists from the U-M College of Engineering — including research scientist Yu-Chih Chen, Ph.D., the other lead author of the study, and Euisik Yoon, Ph.D., professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of biomedical engineering — to develop a microfluidic device, sometimes called a lab-on-a-chip, that would allow them to isolate and study the hybrid cells.

The device allowed researchers to pair a single breast cancer cell and a single mesenchymal-stem cell, and directly observe the engulfment process. The approach also allowed for the selective isolation of cells for additional analysis, Chen says.

Research showed these mesenchymal-stem-cell-eating cancer cells developed significant changes in the genes they expressed, including several known to be involved in metastasis, Kleer notes. And in mouse models, the hybrid cells led to much more extensive metastasis than non-cell-engulfing control cells.

“These findings reveal how the direct interaction of cancer cells with mesenchymal stem cells can lead to the development of aggressive cancer,” Kleer says.

“Not only does this open up new avenues to study the underlying biological mechanisms, but the microfluidic chip and method we’ve developed could be the starting point for a clinical test to help determine the likelihood that a breast cancer patient’s tumor will metastasize,” she says.

U-M has filed for patent protection on the microfluidic device.

Story by Ian Demsky

Originally published by U-M Health Lab

MENU

MENU