How CS is changing education

Embedding coding into high school history class; building eBooks to broaden participation in computing; and rolling out digital tools for collaborative K-5 learning. Michigan researchers are taking on the big challenges to integrating computing into everyone’s education.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Professor Mark Guzdial wants more people to use computing in their work and lives.

“Programming is super powerful, and I want a lot of people to have access to that power,” he says. “Computational literacy is critically important in our world today.”

Guzdial, himself a U-M alumnus, joined the faculty at Michigan in 2018 after 25 years at Georgia Tech. Over the years, he’s established himself as a leading voice in the field of computing education research.

“I’m interested in both the infrastructure that allows us to teach programming to people and to make things accessible in order to broaden participation in computing,” says Guzdial. “But I’m also interested in building the tools and doing the laboratory experiments to come up with deeper insight into what’s going on when students are learning about computing.”

Computational media connects with students

While he was at Georgia Tech, Guzdial and his then-PhD student Andrea Forte (now on the Information faculty at Drexel) were evaluating how Georgia Tech students performed in a required CS literacy course. They recognized that before many students could succeed at computing, they had to see it as useful and connected to their lives. Forte made the observation that for these students, computing was not a matter of calculation but of communication: these students cared about digital media.

So they, along with Georgia Tech researcher Barbara Ericson (who is a Michigan alumna and is now an assistant professor at the U-M School of Information) developed tools to teach programming in terms of what Guzdial calls media computation: how to manipulate the pixels in a picture, how to manipulate samples in sound recordings, and how to manipulate the frames in a video.

It’s relevant, says Guzdial, in the same way a biology class is. “Why do you take a biology class? Because you live in a world full of living things. Why do you take a class in computing? Because you interact in a world increasingly driven by digital media. You should know something about how it is created and structured and how it can be manipulated. That’s what the course became.”

And it worked. “That’s when I realized,” states Guzdial, “that we can change how and what we teach in computing. We can connect by making the tools useful and usable, for both teachers and students.”

Fast-forward to 2020, and Guzdial is creating task-specific programming tools as a complement to media computation. In one project, he’s creating a new programming language that strips away programming syntax and allows users to make a chatbot. He has created chatbots that act as a baby, a toddler, Alexa, and Lady Macbeth.

Enlarge

Enlarge

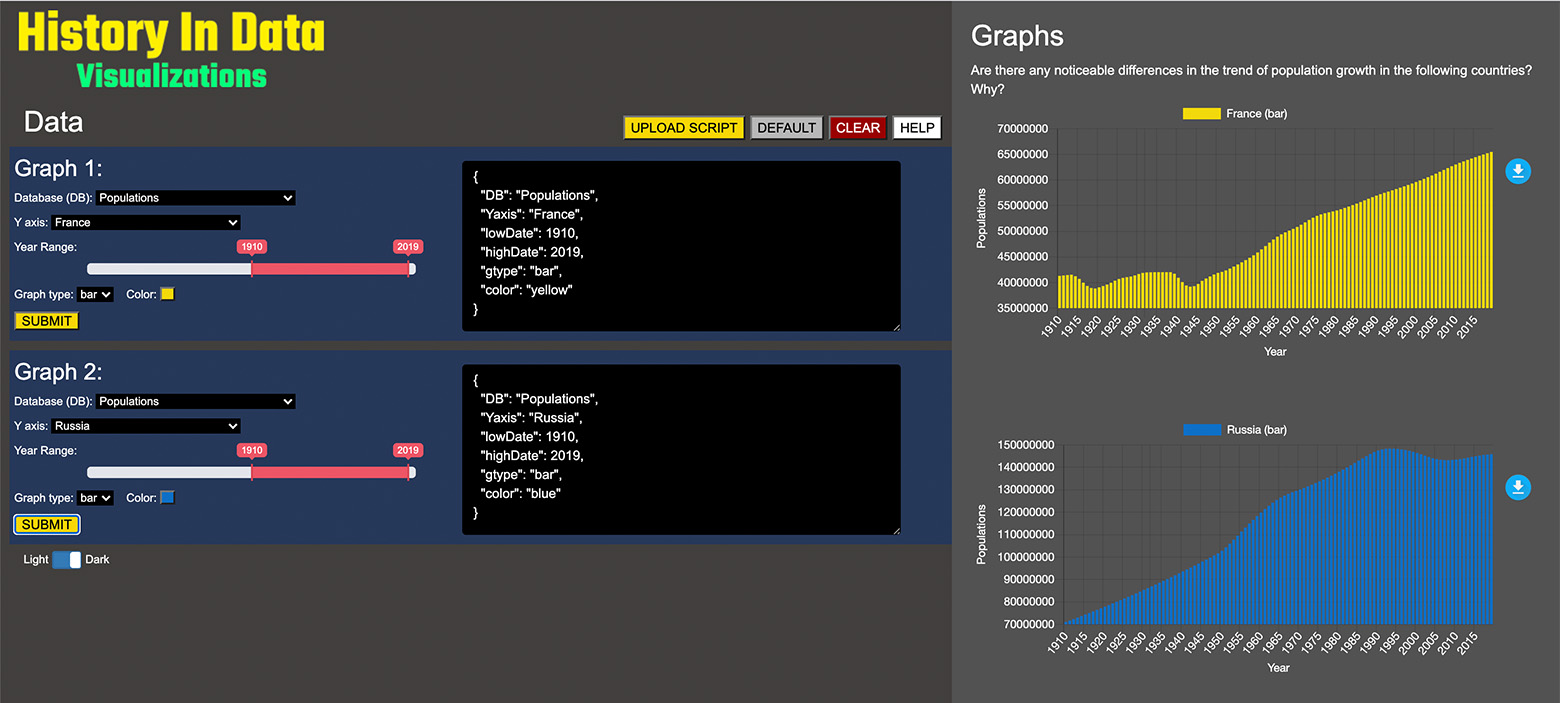

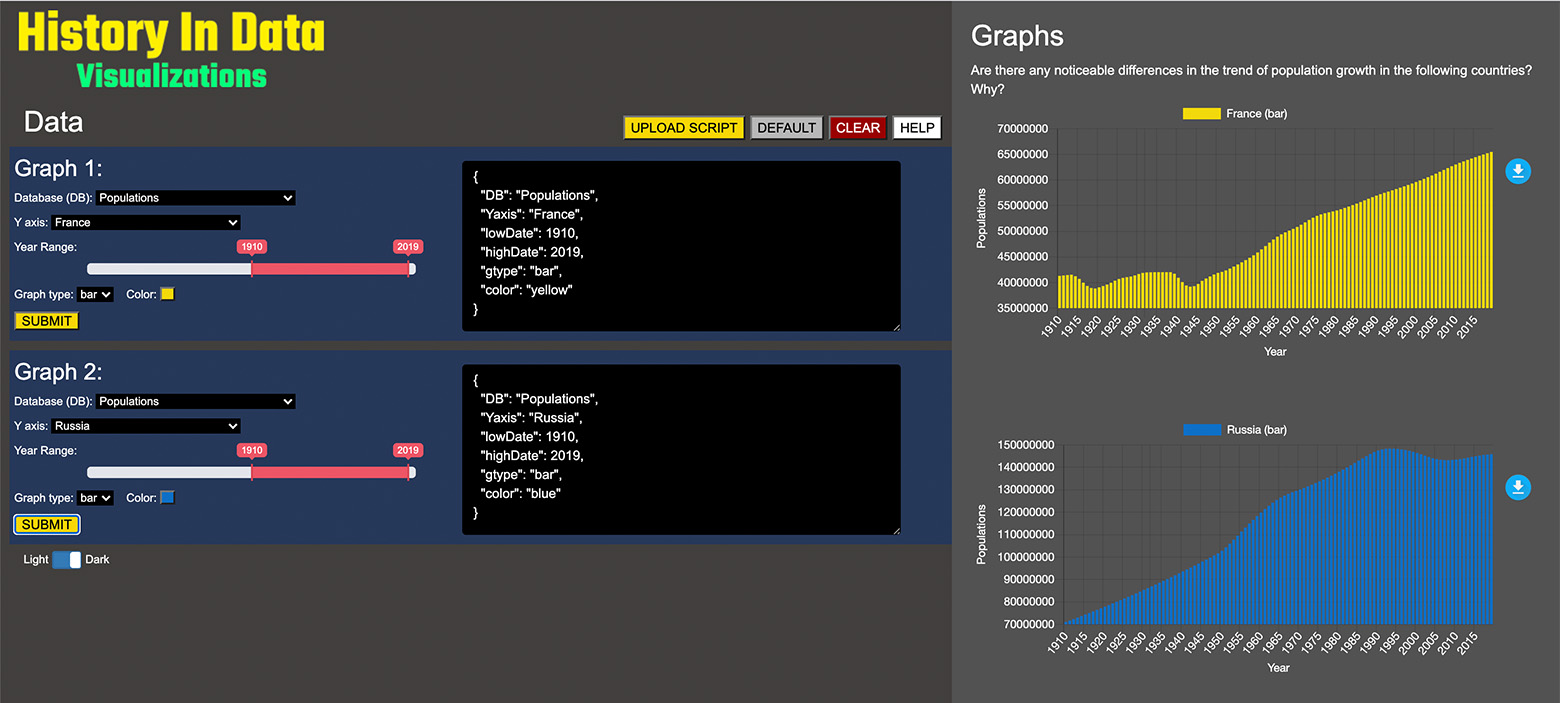

Teaching history with CS

Under a grant from the National Science Foundation, Guzdial and Engineering Education Research PhD student Bahare Naimipour have proposed a new way to integrate the use of task-specific computer science tools into history courses. In this project,they are collaborating with Michigan alumnae Prof. Tamara Shreiner at Grand Valley State, who teaches data literacy to future social studies educators. Guzdial, Naimipour, and Shreiner involve Shreiner’s new teachers in the process to develop curricula that meet teachers’ perceptions of usefulness and usability. High school students who take their courses will learn data manipulation skills as a part of completing their history assignments.

“This project is being built into new, interactive course materials that will allow high school students to build data visualizations in history classes as part of an inquiry process. We use programs to capture the students’ process as they investigate historical questions,” explains Naimipour.

“By doing this,’ adds Guzdial, “CS becomes a tool that students can get comfortable with as a part of their learning. A larger and more diverse range of students will get CS experience, and the use of data manipulation tools will allow them to explore history in a new way. We hope that this type of engagement will lead to a greater level of comfort with and participation in CS courses.”

Over a three-year period, the project will track teachers from Shreiner’s pre-service data literacy course at Grand Valley State University, into their field experience, and on into their in-service placement.

“For the project to be successful, teachers need support to feel comfortable with the new tools and to adopt them in their classes,” notes Guzdial. “For this reason, at the end of the three year project, we will be able to describe the factors that influence adoption and non-adoption, so that we can iterate and improve.”

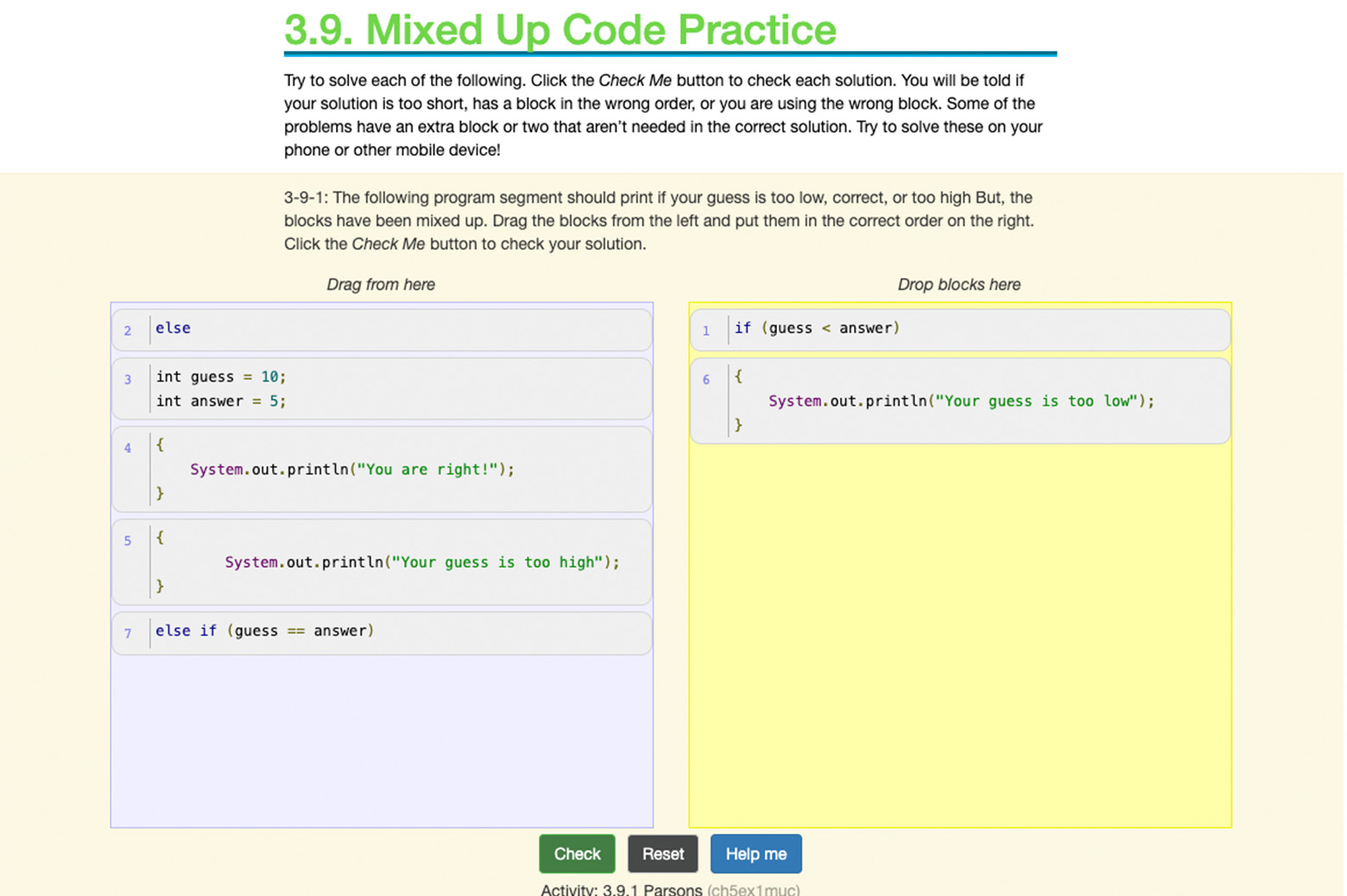

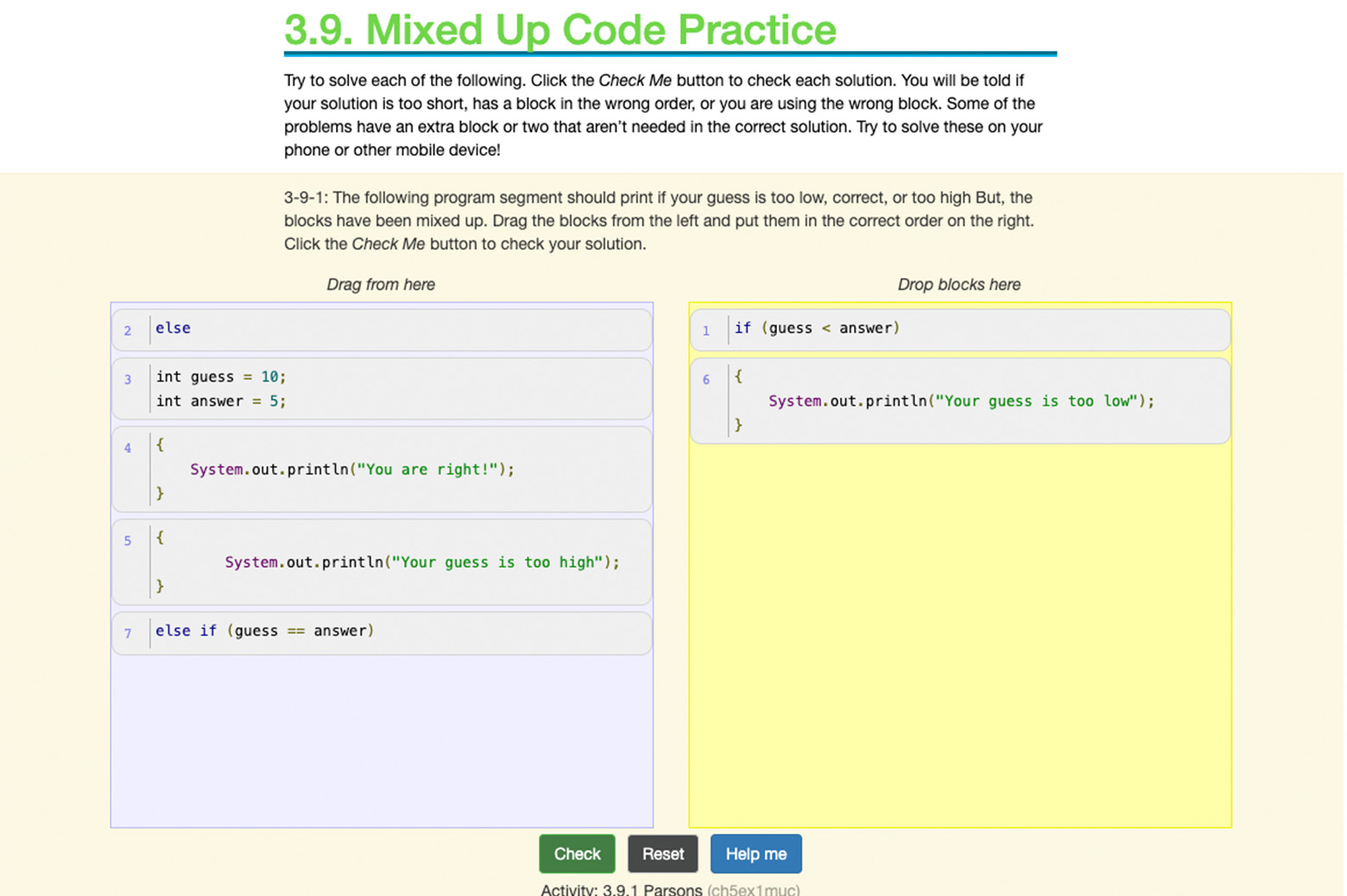

eBooks integrate coding and learning techniques into lessons

“One of the things I’ve found is that high school teachers can only adopt new books about every seven years. So even if I taught them interesting new ways to teach computer science, they couldn’t buy the books for some time,” says Barbara Ericson, who’s on the faculty at the School of Information. “So, that’s part of why I’ve been working to develop free eBooks that anyone can use.”

Enlarge

Enlarge

Ericson has collaborated with Guzdial on numerous occasions, including on a long-term project to improve computing education, from teacher certification to standards – and on media computation. For the media computation project, she wrote the Java book, the visualizer for sound, and other tools. She also wrote many of the exercises. She did a lot of professional development with teachers and got feedback on the tools.

Another project that they began working on together, but with which Ericson took the lead and ran with, is Ericson’s eBooks project. It’s a key part of her focus on increasing participation in CS – a subject she is passionate about.

Students like using interactive ebooks and studies have shown that they have better learning gains than with traditional practice.

“We designed our eBooks based on educational psychology, where more people perform better if they have a worked example or an expert solution followed by similar practice,” states Ericson. “So rather than just providing practice, we have worked examples of code that you can run, we explain the code with textual comments as well as through audio, and then it’s followed by practice, including multiple choice problems, mixed up code (Parsons) problems, and clickable code.

“One of the things we’ve learned in our research is that people – even the teachers – don’t like to read. They immediately skip to the problems and then go back to the text if they need to. So we don’t have much text: we have some bullet points and examples, and then we go to the interactive examples.”

Ericson can monitor how people use the eBooks through log-file analysis. She can look at which questions people are able to answer correctly, and where they struggle. This allows for continuous improvement.

“Interactive ebooks are going to be the future. They’re much easier to change and improve,” says Ericson. “And they could increase success in CS.”

Ericson has developed three eBooks to date: two for high school AP CS, and a new one that is debuting at U-M this Fall in SI 206 (Data-Oriented Programming). James Juett, a Lecturer in CSE who is teaching ENG 101 (Thriving in a Digital World), has also created an eBook on MATLAB, following Ericson’s approach, which he is using in his class this Fall. There are over 25,000 registered users for CS Awesome, Ericson’s AP A eBook, and over 1,800 teachers in a users group.

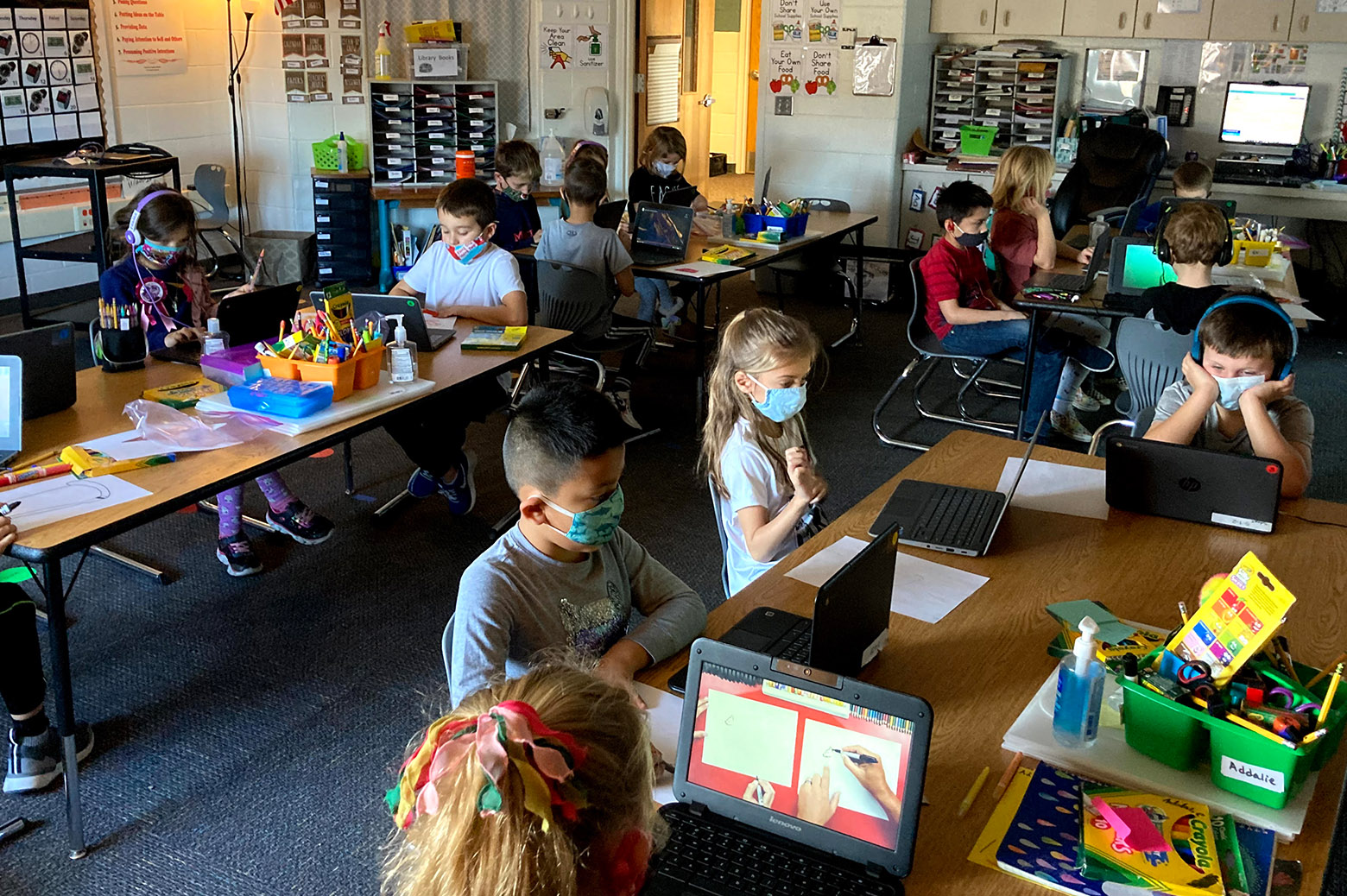

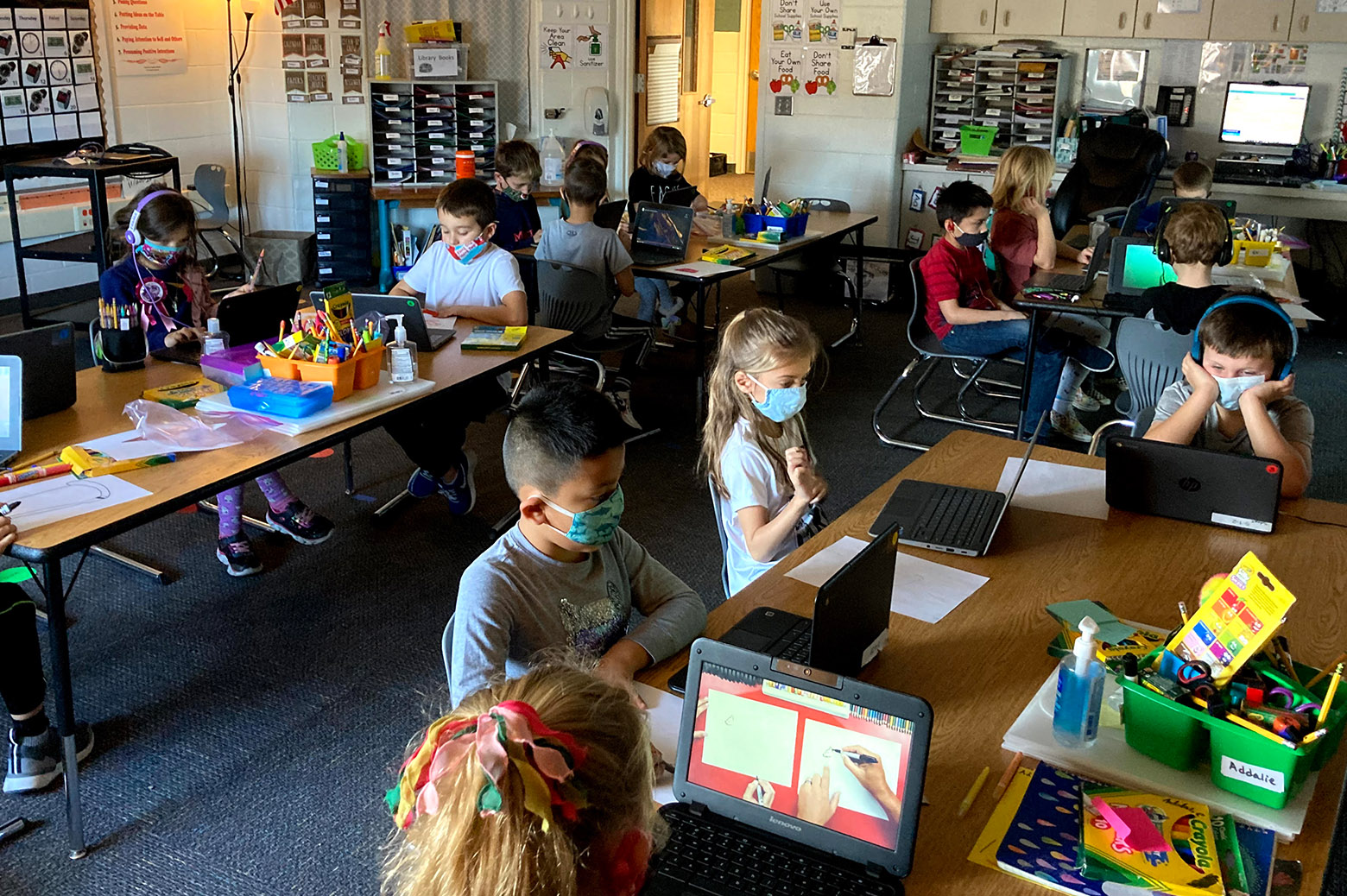

A collaborative, digital platform for K-5 learning

For many years, Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Elliot Soloway has been hard at work to transform K-12 education with collaborative digital tools. Now that we’re faced with the COVID-19 pandemic, it turns out that his prescriptions are just what the doctor ordered.

Soloway has long advocated a more exploratory and collaborative approach to learning, enabled by technology. As far back as 1990, he was merging education and tech in a project at Ann Arbor’s Community High School, where students conducted on-the-street interviews and used Soloway’s tech to create full-color multimedia lab reports.

An AI researcher by training, Soloway recognized early on the need for a collaborator in the education space, and in 2011 he teamed up with Cathie Norris, Regents Professor in the Department of Learning Technologies at University of North Texas in Denton. The two have published, experimented, and advocated together since.

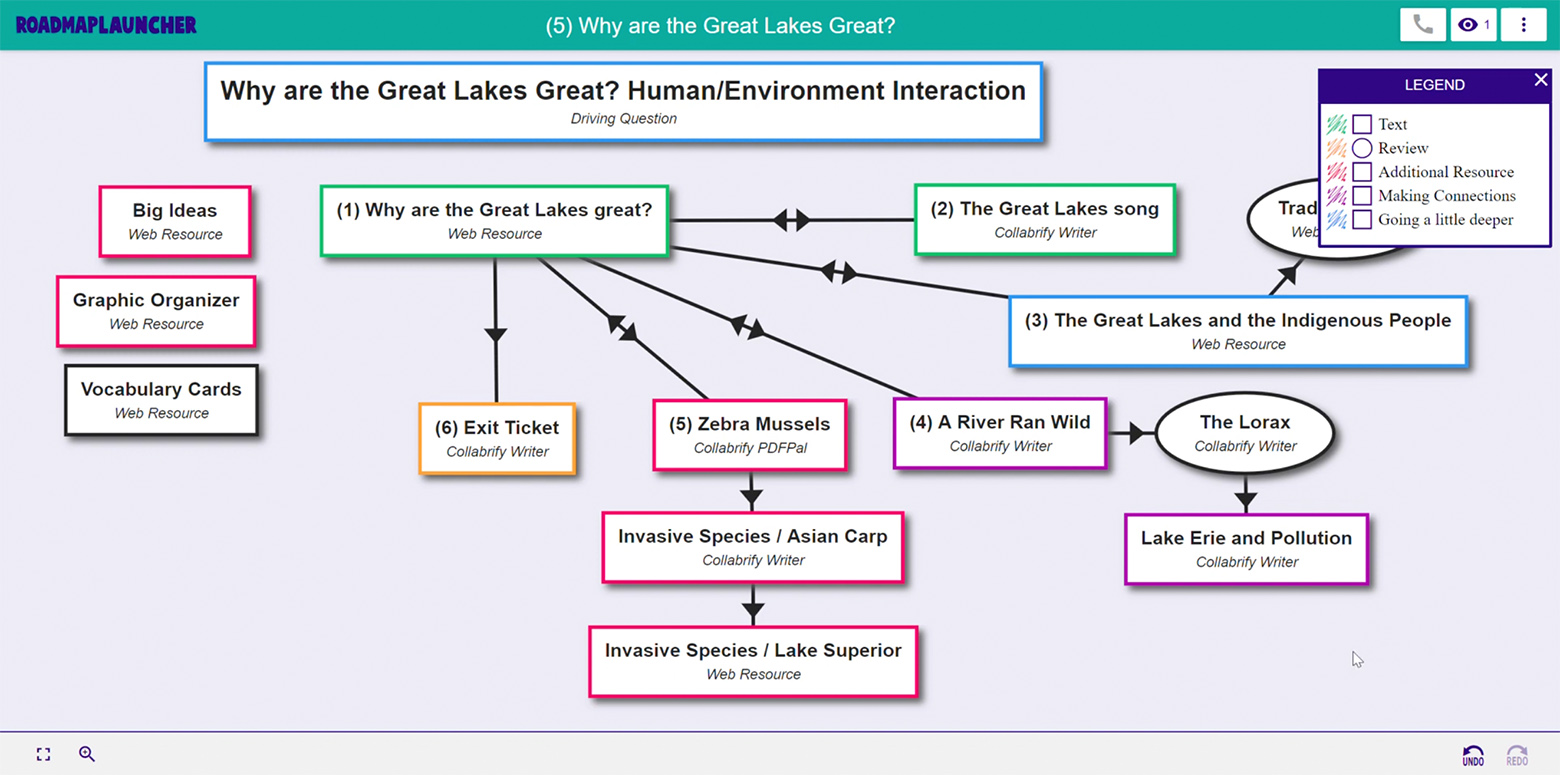

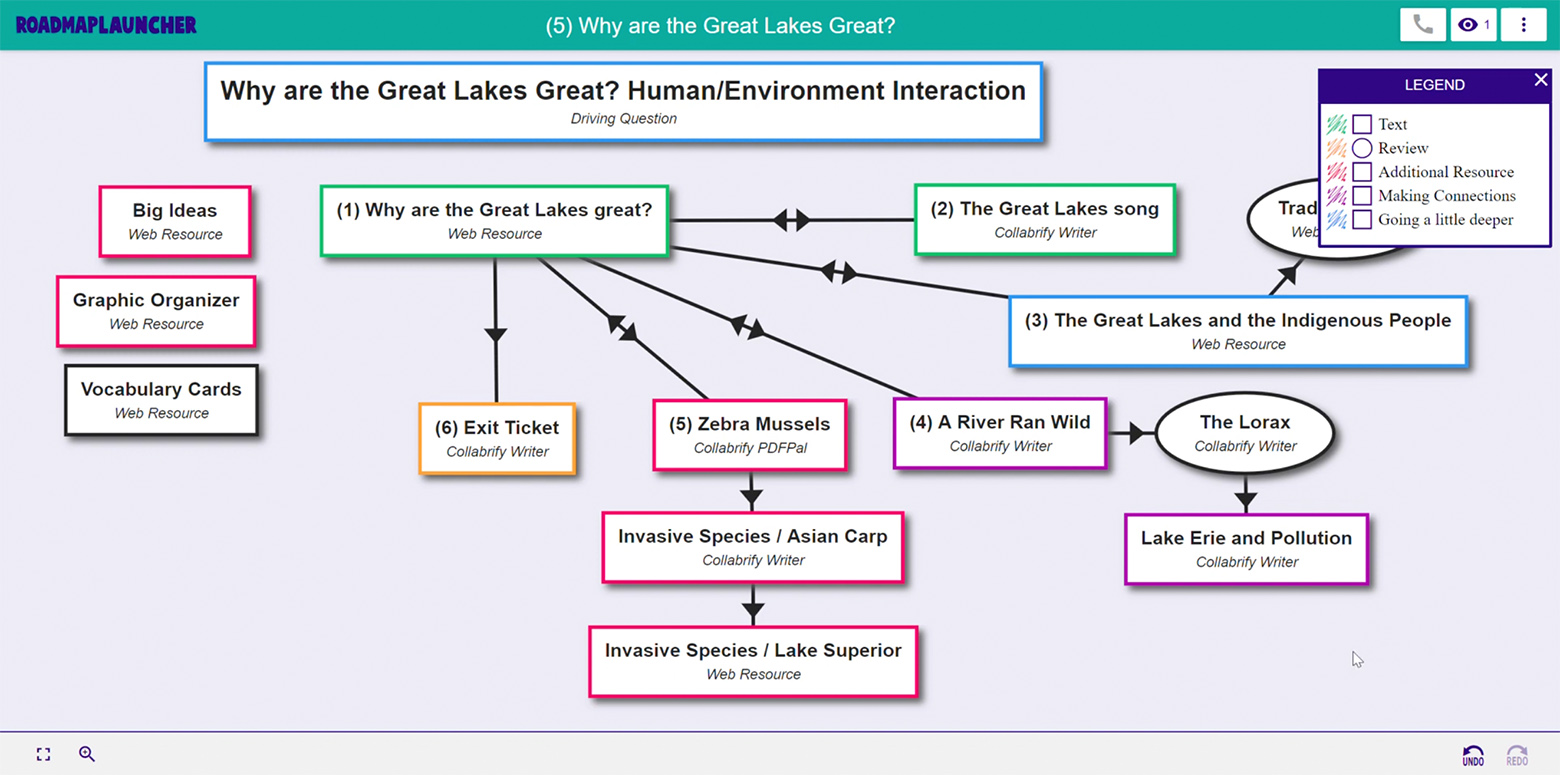

In 2012, Soloway and Norris began work on a digital learning toolset, called Collabrify, that has now emerged as a web-based platform they see for transforming how students and teachers interact to explore, learn, and guide.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Today, the Collabrify Roadmap Platform is the vehicle used to deliver curricula through Soloway’s and Norris’ new Center for Digital Curricula (CDC) at U-M, which launched in the summer of 2020 to provide free, deeply-digital standards-aligned curricula for K-5 (the area of greatest need, according to Soloway). And although the vision for collaborative online learning and its benefits pre-date the COVID-19 outbreak, Collabrify and the CDC have arrived at an opportune time.

The Collabrify Roadmap Platform is a set of free, customizable digital learning tools that allows students to work individually or in groups using mobile devices or laptop computers. Roadmaps provide teachers with scheduling templates that can be customized to include all the activities that would normally take place in their classrooms. The system guides students through the day, points them to the resources they need to complete their work and enables them to collaborate with teachers and each other. The platform also provides a searchable repository of online lessons developed and vetted by teachers, which is also distributed for no cost.

Wendy Skinner, who teaches second grade at Brandywine Community Schools in Niles, Michigan, says it’s a significant improvement over other attempts at K-12 online platforms, which aren’t designed to be as comprehensive, intuitive, or engaging.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“Roadmaps are the only thing I’ve seen where I can plug in my skills for my kids in the way that I’d do it in the classroom,” Skinner says. “The kids have a schedule, and there’s a nice visual finish and sequence to it. It’s all in one place and I can monitor it and look at what they’re doing. I can make sure that it includes the things that I value and make my connections with the kids meaningful.”

While tools like Google Classroom can help streamline classroom logistics like grading and file sharing, Soloway explains that aside from Collabrify Roadmaps, there is no single, reliable source for managing digital curricula. “One of the important takeaways is that our center is providing not only the platform – we’re also providing the standards-aligned deeply digital curricula that teachers can customize to their needs.”

“A lot of schools have attempted to arm their kids with some type of digital device to assist in learning – a Chromebook or a tablet,” says Don Manfredi, a mentor-in-residence at the U-M Office of Technology Transfer who helped launch the CDC. “But the content to actually take advantage of these devices was very far behind. So the idea was, let’s provide teachers with a deeply digital curricula to make these devices more valuable to the kids. And with COVID-19, it’s just gotten pushed to the forefront.”

And what does “deeply digital” mean? It’s not just a pdf of a textbook. It’s the ability to use an integrated suite of technologies as part of a platform to plan, explore, interact, collaborate, and create.

The CDC relies on a core group of Michigan teachers who create and vet digital content in addition to their teaching duties. Skinner and over 100 other Michigan teachers are now using those materials, and some of them have stepped up to create new digital content which is now available on the repository.

The CDC recently received a grant from Twilio, which has enabled the ability for kids to quickly talk to each other. In a classroom, they can “Turn and talk” with a classmate. The new feature provides voice over IP to allow for the same type of spontaneous communication. “Some students could be in class, some could be at home, or they could all be remote,” says Soloway. “The kids don’t need phones – they can just talk to classmates through Collabrify.”

Collabrify also provides the ability for teachers to monitor in real time what students are doing, and now with the talk feature they can also speak to students at the same time. Instead of handing in material for grading, teachers can interact with students to correct or reinforce in real-time, while the students are working on the assignment. Formative assessment like this has been shown to improve performance by 2-3X, according to Soloway.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Among the many challenges related to K-5 education this year is the ability to deliver curriculum electronically to students in a format that they can master,” says Pamela Thomas, Elementary Principal at Kent City Community Schools. “Roadmaps has proven to be a powerful tool, yet simple enough for our youngest students to access learning. Teachers are able to create their own lessons, or access curriculum and share it with students in a way that is both engaging and easy to navigate.

Students have responded well to the system, including seventh grader Jillian Biewer, who attends Marysville Middle School in Marysville, Michigan. She particularly likes the BrainVentures exercises, which offer an opportunity to learn across multiple disciplines and collaborate with friends even though she’s isolating at home.

“When I’m doing a BrainVenture and I’m talking to people, it makes me feel closer in a way, like they’re there right next to me doing it with me,” she said. “It’s almost therapeutic because when I’m doing it, I’m not worrying about what’s going on around me, I’m not worrying about the news, I’m just learning in a fun way.”

MENU

MENU